| I

was born in Douglastown in 1870. My father was Andrew Rooney, my mother Jane Sprune, both born in Douglastown. My whole lifetime was spent here. I was christened by Rev. Father Saucier; godfather was William Rooney, a cousin of mine; godmother was Ann Rooney, my father's sister. My school days were very short. I left the classroom at twelve years of age and made my first Communion that same year. The priest in charge of the parish at that time was Rev. Father Guyard, replacing Rev. Father Gillis who was visiting the Holy Lands. |

|

| My

mother, Jane Sprune, had four sisters and one brother. Sisters: May Sprune (Mrs. James Maloney) Charlotte Sprune (never married) Susan Sprune (never married) Brother: John Sprune. My grandmother was a Johnson. one of the first settlers in this parish, and she received from the government practically one quarter of all the land now known as the parish of Douglastown. The name of Sprune has died out with the passing of my uncle John Sprune in 1923. |

|

In my family there were five boys and two girls. Girls: Mrs. Horatio Holland (Caroline), no family. Mrs. Arthur White--(Hilda May). four sons: Boys: Myself. William Rooney, married Clementine Conley. Zeno Rooney, married Clorendia Maloney, Thomas Rooney. never married, lived and died in British Columbia. Joseph Rooney, never married, died at the age of thirtyseven at home. John Allen Rooney. never married. |

|

| Caroline Rooney, Phil Legros and Oley. |

| My

wife was Clementine Conley, born in Douglastown in 1869;

her father was Thomas Conley; her mother Julia Maloney: she had five

sisters and four brothers; and she is the only one of the family who

is still living. Following are the names of her sisters and brothers. Sisters: Mrs Richard Briand (Julia), had six children two of whom are still living. Those two are Mrs. Roland Vautier (Gladys) of Shigawake East. and Emmanuel Briand of Douglastown. Mrs. Wilfred Fitzpatrick (Florence) of Gaspe, died at the age of thirty-three leaving eight children. Two other sisters died at the ages of six and four. Brothers: Michael Conley, married Nora Morris, had no family, died in 1961. Patrick, John, and William died when they were children: thus the Conley name has also died out. |

|

|

Nora Morris.

|

My

wife's grandfather was from Belfast, Ireland, and his wife,

Ann Watson ran away from home in Scotland to marry Bernard Conley who

was a Catholic. Her father refused his permission to the marriage, for

he was of high rank and not a Catholic.

Bernard Conley was a captain of the militia and a close friend of Queen

Victoria, with whom he corresponded very often, and from whom he received

a small pension.

He had two children when he came to Canada, James and Catherine, and two

were born after he came here, Thomas and Mary Ann Jane.

Bernard Conley had been a school teacher in Belfast, and he also taught

school in Douglastown. In his time the priest could get here very seldom,

so Mr. Conley would gather all the people to the school~house and say

the Rosary on Sunday mornings

My wife was baptized by Rev. Father Winters. She was carried a distance

of three miles by the godmother, Mrs. Michael Rooney (Mary McAuley). Seal

Cove River had to be crossed, and the only way over was one stringer on

which to walk: that was not too safe with a swollen stream, on May 8,

1869 - a hard voyage with a tiny infant. The godfather was Xavier Kennedy,

who later became the member of parliament for Gaspe district.

The Church of the wedding (1898) |

The

school teachers at this time were many. My wife

left school at sixteen, later worked in Montreal as cook for an

elderly couple for seven years, the use of electricity was beginning

to originate in Montreal in 1895; before that the heating had been

from coal. In summer gas had been used for cooking, and light had

been from gas. |

Jerome Morris. |

I had begun

a life of hard work at the age of twelve.

I began to fish -the main fishing grounds was Anticosti Island - leaving

home about the first day of June, to return in the early part of October.

This was the only means of livelihood; so each man built himself a boat.

took his sons, if he had any, or got a neighbor to join him in the season's

catch. The food consisted of dry hard biscuit and cold water during the

fishing hours. When the day's fishing was over each man had to split and

make his own fish and cook a supper of fish and potatoes, the potatoes

being taken along from home. Hard biscuit was the desert during the fishing

season: bread was not to be had until we returned in autumn to our homes.

Usually a young boy or an old man was kept to spread and turn the fish

on flakes made of dry boughs, while the good, smart and healthy men fished.

The price of dried fish in 1882 was $2.75 per cwt., and it was $4.00 for

a barrel (200 lbs) of good salt herring. One could not "jump" the job

to search for another one; there was no better one, but there were very

few complainers -each man did his work and always found time to have a

smoke from "leaf tobacco" that raised a strong odor but was greatly enjoyed,

while a good old story was related by one of the fishermen, or trick was

played on one of the men. The money received from a summer's catch scarcely

covered our expenses; it was next to starvation.

The winter presented just as serious a situation, but with

one comfort, a home to sleep in and a wife or mother to prepare the meals.

An ox was the only working animal; lucky was the man who could afford

to keep one. I remember one man who kept his ox by the side of his house

all winter, too poor to have a stable; if the wind blew north, he tied

the ox on the south, if the wind blew east. he put the animal on the west

to shelter him.

Railroad ties and long lumber were the only sources of income during winter.

With a slow ox, long distance and bad road a man had to start at five

in the morning and return home at night long after the stars were shining,

if he wanted to keep "the wolf from the door." as was the saying then,

for railroad ties sold at $0.10 each, and a good day's work was eight

ties. Long lumber was sold according to the size of the top: if seven-inch

$0.07 a foot, if eight-inch $0.08 a foot, and so on. It must be remembered

that about six and a half to seven miles was the distance we had to go

before we got to our work, the same distance to come back at night.

When spring came some of the logs cut during winter were sawed by hand,

what we called whip-sawed, and the boards were used to make drums and

tubs. It was not easy, but it was the best part of our year, at home,

to work at those, which were sold for $0.25 a tub and $1.00 a drum. But

the heart-breaker was we were never paid a cent for any of our work, summer

or winter; we were given a credit slip, called a "beau", that was presented

to the merchants when we needed food or things that were available. There

was no "serve yourself counter". The men were not educated; so it is only

the good Lord who knows how much was missing on our "beaus".

About the year 1912 the "fishing life" was a little brighter.

The main fishing place was St. Yvon. There we could get

money for fish, as much as $13.00 a cwt., and could have our bread baked

by one Father Deanna Gillis construction, bringing many strong men here

employed by the Canadian National Railway, and all receiving good wages.

They eagerly purchased the hand-made articles at the bazaar to the joy

and relief of the hard-working parishioners.

DISASTERS

On June 6. 1914, a terrible snow-storm struck and many farmers lost their sheep which had been out on feeding-ground, for about two feet of snow fell. Two large ships, that were loading with railroad ties and were anchored in Douglastown Bay, came ashore on the beach and remained five days before being towed away by tugs.

The year 1901 was a sad one for this town. The scarlet fever raged all winter, but when the heat came it got worse and claimed many lives, especially children. Three died in my wife's family alone.

In 1914 the Spanish Influenza was another disaster that left many a sad family. The temperature of victims of this plague rose so high and lingered so long that the patient would be delirious for days and with some it remained weeks. Neighbors were afraid to go and help, and in some homes the entire family was bedridden at once; hence there was no one to make a fire or pass a drink. The persons that died from this were not taken into the church for funeral services, the disease was too contagious: so the orders of the doctors had to be carried out in this respect. It was very sad, and we read that this epidemic took more lives than the First World War

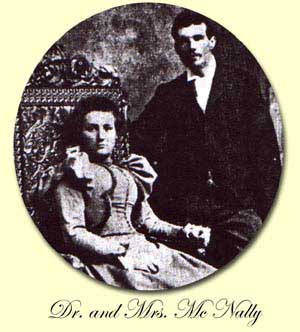

| Doctors were hard to get, but Dr. W.J. McNally of Barachois was a very faithful friend to the Douglastown people. He always came, risking his own life, in storms, driving a distance, more than twenty miles with a horse, an roads that if people of today were asked to pass on would certainly cause a lot of complaining. I Dr. and Mrs. McNally of the parish women and washing done also. That meant a life of luxury to what we had experienced in past years. Clothes could also be bought in the local stores; fishing boots knee-high were sold for $4.00 and pants $2.00 a pair. |

|

During one winter I was hired in the late Mr. Robert Linsey to care for the animals and cut the wood needed for heating the house. The wages at that time was $20.00 for the season, this included doing the spring ploughing and seeding. Carpenter's wages was $0.50 a day. The same clothes were worn on Sundays and weekdays, and there was no Choosing what to wear: every man was the same. In those days two men would go by boat to Percé bring a barrel of flour, and divide it among several families.

Enjoyments were few in my young days. Winter was the only season that afforded some excitement. If we could persuade some family to make a "wood-hauling party", our good will was aroused, wood was cut and hauled all day, with no thought of fatigue, and at night the ladies gathered, the men forgot their day's work and just settled themselves for a big night of fun and dancing. During the day one man would volunteer to drive to Gaspe to Mr. LeBoutillier's and buy a supply of whisky for the other men, while they cut and hauled a share of wood for him, The party went on till morning, and every person had a good time. Sometimes a fight started, but it never lasted and no grudges were held, Another kind of party was a raffle; the ticket or dice-throw was put up generally on a "hat". While some danced, some threw dice, others chatted, the night passed, a lunch was served, the music was free, and no one ever saw the "hat". But no complaint was found as each one figured he got plenty of enjoyment for his quarter.

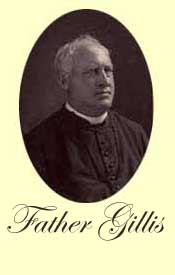

The priest that used to come to Douglastown was from Percé and that was only once a month. The first one I remember was Father Moreau, whom I was very interested in because of snipe hunting trips we would take together on the marsh, I had a big dog that would gather the snipes as Father Moreau shot them, this was about the year 1880. Several priests were here for short periods. until Rev. Father Gillis came to remain. He was parish priest for many years and died here.

| Father

Gillis's rectory was in need of a veranda,

so the ladies of the parish decided they would do their share to make him comfortable; they organized a bazaar, and did a wonderful job - my wife was organizer. During that year. 1910, the railroad was under Elections were not of much interest to the working-man. No one held a government position except a light-keeper. and those were very scarce. At election time the merchants would dictate how was the best way to mark the ballot; a couple of glasses of whiskey were served on the sly, and that did the trick. |

|

| Father Duncan Gillis |

Progress came slowly, In the years previous to 1911. when no train united our town with other places, and the shipping season was closed, the only way for people to travel or to get provisions was to drive to Campbellton with a horse, about two hundred miles. Mr. Martin McCabe and Mr. John McDonald made several trips over this perilous route. The mail was transported in this manner summer and winter.

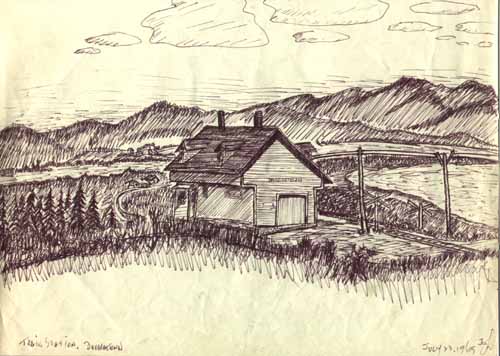

| In 1911, when word went around that the train was to make its first appearance, young and old made their way to the railroad track in order to witness for themselves their heart's desire come true. The wonderful thing the Canadian National Railroad would be to those poor hard-working Gaspesians could hardly be put into words. to know that all the little villages would be joined together and no more need to worry about supplies and provisions in the long stormy months; in time of sickness a doctor could be reached or a patient could be even taken right to Montreal!!! |

|

Under Premier Taschereau the roads were repaired and gravelled, so that a car could drive along the main route at a slow speed, providing all the passengers were in good health and able to stand a good shaking, but it was such a change from the old trails that people were delighted over the whole affair. As time went on and Maurice Duplessis was Premier, more money was in circulation, income tax was in force and the people began to see improvements which have continued and likely will, no matter what occurs. The hard slavery days will never come back, because people are educated and will not stand to be imposed upon as they were in my childhood.

| When we stop and think of all the improvements that have come our way in one life-time, we imagine it must give great courage to the younger generation, to carry on the great work that has been nobly handed down by so many good and honest men of the early years: "Never give tip, but with head held high do your part, for God and Country." |